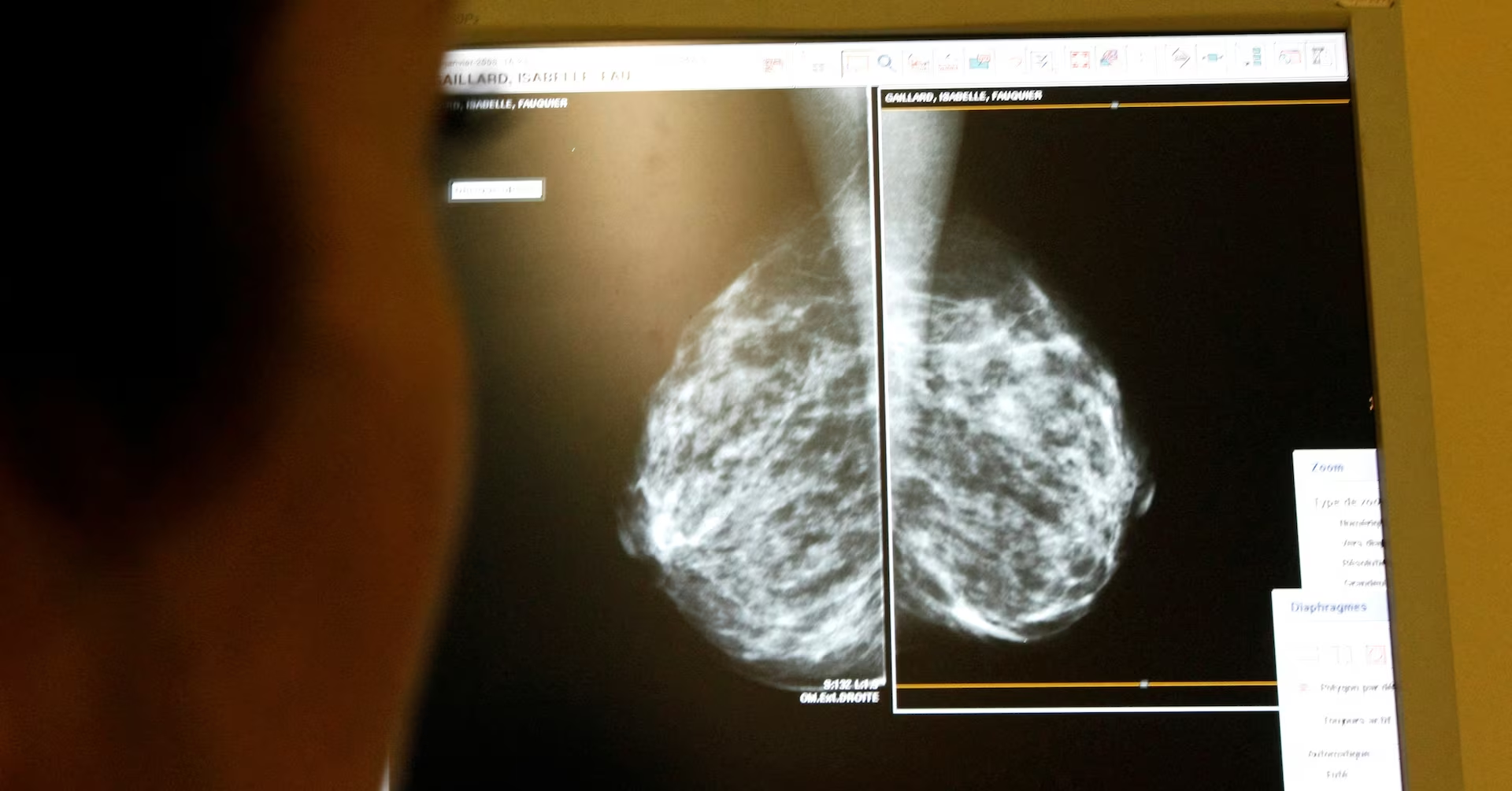

A groundbreaking study published on Monday has identified twelve breast cancer genes in women of African ancestry, potentially enhancing risk prediction and shedding light on distinct risk profiles compared to women of European descent.

While previous research predominantly focused on genetic mutations associated with breast cancer in women of European ancestry, this study encompasses data from over 40,000 women of African ancestry across the United States, Africa, and Barbados, including 18,034 individuals diagnosed with breast cancer.

The findings reveal mutations previously unrecognized or weakly linked to breast cancer, suggesting possible differences in genetic risk factors between women of African and European descent, as detailed in Nature Genetics.

One newly identified mutation demonstrated an exceptionally strong association with the disease, underscoring the significance of these findings in cancer genetics.

Interestingly, certain genes implicated in breast cancer risk among white women showed no association in this study, highlighting potential disparities in genetic susceptibility.

Black women in the United States face heightened breast cancer risks, including earlier onset and higher mortality rates compared to white women, underscoring the importance of tailored risk assessment and intervention strategies.

The study’s researchers developed a breast cancer risk score incorporating the newly identified genes alongside established risk factors like BRCA1 and BRCA2, significantly improving risk prediction accuracy for women of African ancestry.

Six of the identified genes were linked with an increased risk of triple-negative breast cancer, a particularly aggressive form of the disease prevalent among Black women.

Further evaluation is necessary to assess the clinical utility of these genetic variants before routine testing can be implemented, according to Dr. Wei Zheng, the study’s lead researcher from Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

While genetic testing is recommended for all breast cancer patients regardless of race, disparities persist in access to such testing among Black women in the United States, primarily due to differences in physician recommendations and healthcare access, according to the American Cancer Society.