India has refused requests from pharmaceutical companies to extend a year-end deadline to upgrade their manufacturing plants to World Health Organisation (WHO) standards, following the deaths of at least 24 children who consumed contaminated cough syrup, sources told Reuters.

In late 2023, New Delhi mandated that all drugmakers meet international manufacturing norms, including stricter controls to prevent contamination and ensure sample batch testing. The directive came after India-made cough syrups were linked to more than 140 child deaths in Africa and Central Asia, severely tarnishing the nation’s reputation as the “pharmacy of the world.”

While large manufacturers met the June 2024 compliance deadline, smaller firms were given until December 2024. However, several pharmaceutical lobby groups sought another extension, warning that the cost of compliance could bankrupt smaller players.

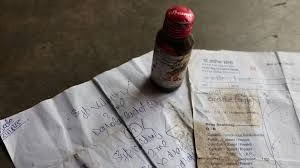

That appeal was rejected after it emerged that Sresan Pharmaceutical Manufacturer, the company behind the Coldrif syrup linked to the latest fatalities, had not upgraded its facilities, three officials said. Tests confirmed that the syrup contained toxic levels of diethylene glycol (DEG) — nearly 500 times the legal limit.

Officials made the decision in October, and drugmakers were informed at a conference last week. The government also revoked Sresan’s license, banned its products, and arrested its founder, S. Ranganathan, on charges of manslaughter.

Government inspectors found the company’s Chennai-based plant unfit for manufacturing, describing it as a “ramshackle shed-like structure” with “numerous critical violations.”

Toxic Contamination and Tragedy

Tests revealed that Coldrif syrup contained 48.6% diethylene glycol, a chemical that can cause kidney failure and death. DEG is sometimes illegally or accidentally substituted for costlier pharmaceutical-grade solvents such as glycerine or propylene glycol.

A presentation by the Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission (IPC) in October highlighted that contamination may result from “deliberate adulteration or accidental mix-ups” in poorly maintained facilities. Following the tragedy, the IPC ordered manufacturers to test oral liquids for DEG and ethylene glycol before sale.

Among the victims was 3½-year-old Mayank Suryavanshi from Madhya Pradesh, who died of acute kidney failure after consuming the syrup. “We never imagined a simple medicine could turn life-threatening,” said his father, Nilesh Suryavanshi, adding, “My child should be the last. The government must ensure no other parent suffers like this.”

Industry Pushback and Government Response

India’s $50 billion pharmaceutical industry, comprising over 3,000 companies and 10,000 factories, has warned of severe disruptions if smaller firms cannot meet the deadline. Jagdeep Singh, Secretary of the SME Pharma Industries Confederation, said nearly half the drug units in Himachal Pradesh could close, leading to “shortages, unemployment, and national losses.”

However, regulators appear unmoved. “The deadline cannot be extended again and again — people are dying,” one government official said, adding that larger manufacturers that have already upgraded their plants can meet the supply gap.

Crackdown and Local Fallout

Authorities have deployed regional drug inspectors to seize suspect cough syrups and collect random samples. Several pharmacies in the Parasia region of Madhya Pradesh have been temporarily shut for failing to produce documentation for Coldrif sales.

Health workers have begun door-to-door campaigns urging residents to surrender any remaining bottles of the syrup.

Local doctor Praveen Soni, who prescribed Coldrif to several victims, has been arrested as part of the manslaughter probe. He previously claimed it was “difficult to link the deaths to Coldrif because it had been prescribed for a decade.”

Grieving parents, however, say trust has been shattered. “The medicine turned into poison and killed my daughter,” said school teacher Sushant Kumar Thakre, whose two-year-old daughter, Yojitha, was among the victims.