Astronomers have potentially uncovered a rare intermediate-mass black hole (IMBH) lurking on the outskirts of a distant galaxy—an elusive type of black hole that could help bridge the gap between the smallest stellar remnants and the supermassive giants at galactic centers.

The object, named NGC 6099 HLX-1, was detected through a joint effort using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and the Chandra X-ray Observatory, along with follow-up observations from ESA’s XMM-Newton satellite.

Located in a compact star cluster about 40,000 light-years from the heart of the galaxy NGC 6099—itself roughly 450 million light-years away in the constellation Hercules—HLX-1 has displayed a distinct X-ray flare, a hallmark of black hole feeding behavior.

A Missing Link: Intermediate-Mass Black Holes

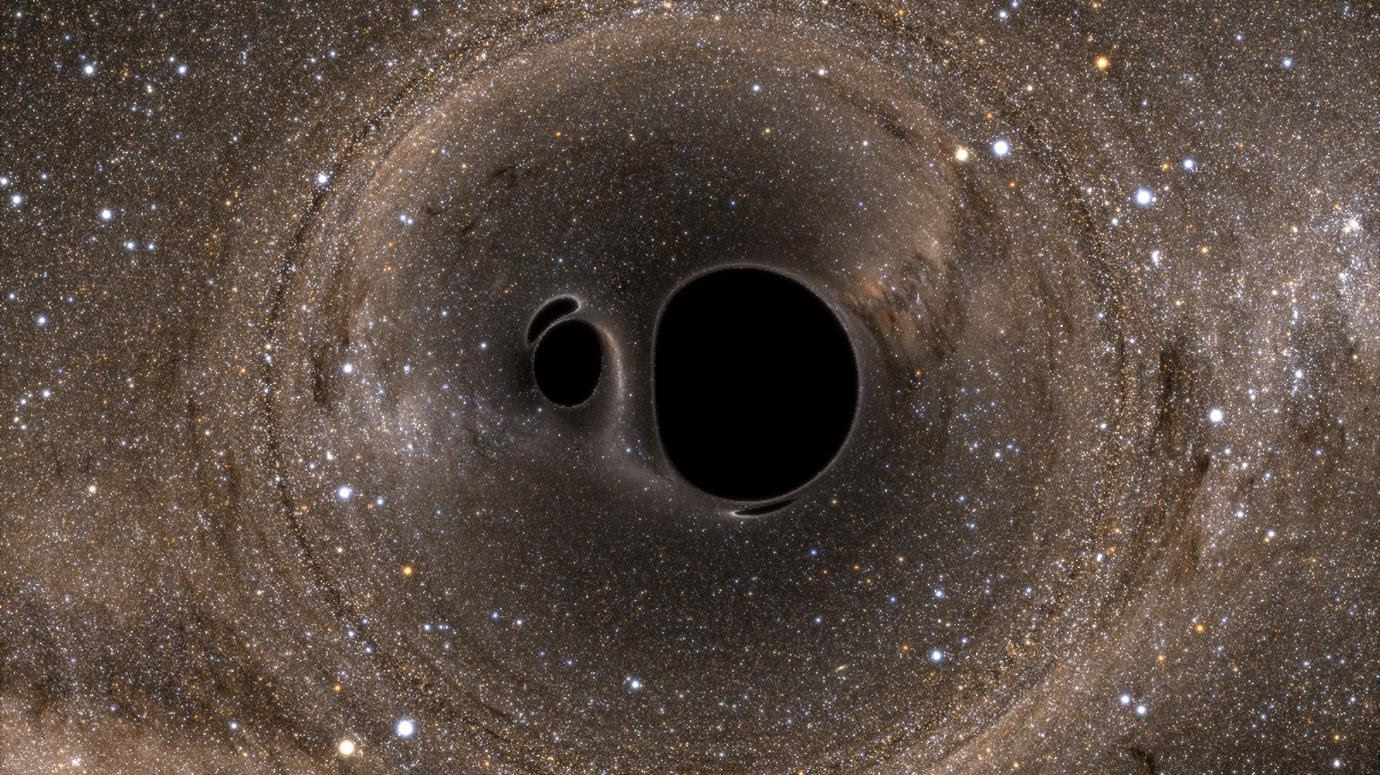

Black holes generally fall into two known categories:

- Stellar-mass black holes, up to ~100 solar masses, formed from dying stars

- Supermassive black holes, with millions to billions of solar masses, found at galactic centers

But intermediate-mass black holes—ranging from hundreds to hundreds of thousands of solar masses—have remained extremely difficult to confirm. IMBHs are thought to play a key role in galactic formation and evolution, yet few candidates have been found.

One reason? They’re often dormant, accreting very little matter and giving off minimal light. They’re virtually invisible—unless a nearby star strays too close.

Caught in the Act of Feeding

Astronomers believe HLX-1 may have been caught during a “tidal disruption event”, where the black hole tears apart a passing star. The resulting superheated debris forms a bright plasma disk, emitting powerful X-rays.

Chandra first picked up the flare in 2009, with XMM-Newton tracking its evolution. The object dramatically brightened—by nearly 100 times—in 2012, before gradually dimming again. This pattern is consistent with a black hole consuming stellar material over time.

“If the IMBH is eating a star, how long does it take to swallow the star’s gas?” said Roberto Soria of Italy’s National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF). “In 2009, HLX-1 was fairly bright. Then in 2012, it peaked. And now it’s fading. We need to see if this is part of a recurring cycle—or if it’s slowly going dark for good.”

Why This Matters

If confirmed, HLX-1 could offer vital clues about how black holes grow and how galaxies evolve around them. IMBHs may represent the “seeds” from which supermassive black holes form, making them a key piece of cosmic history.

For now, astronomers continue to monitor HLX-1 for further flares or long-term decline. Either way, it could be a rare window into one of the universe’s most mysterious missing links.