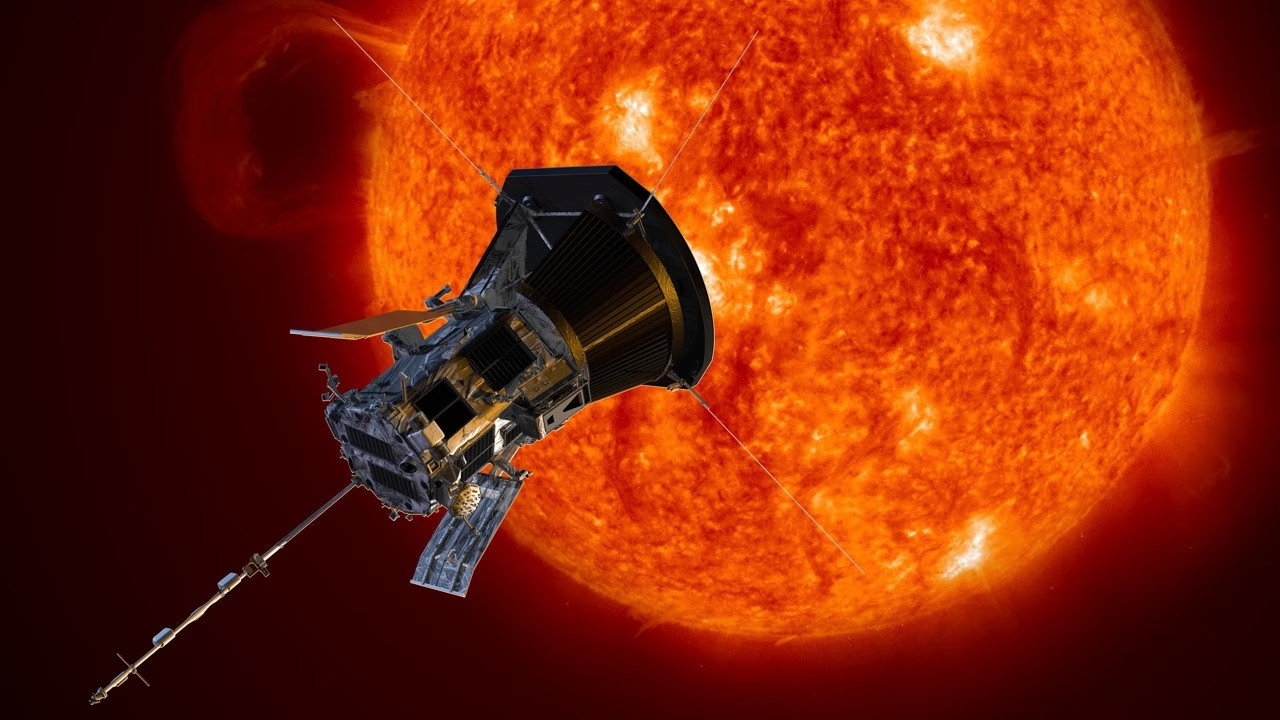

NASA has released the closest-ever images of the Sun, captured by the Parker Solar Probe during its historic close approach on December 24, 2024. These groundbreaking visuals show eruptions of plasma, streaming solar wind, and dynamic coronal activity, offering scientists an unprecedented look at how our star behaves.

A Scientific Milestone

“This is what we’ve dreamed of since the late 1950s,” said Nour Rawafi, project scientist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. Launched in 2018 and named after physicist Eugene Parker, who first theorized solar wind, the probe now comes within just 3.8 million miles of the Sun’s surface — equivalent to half an inch if the Sun-Earth distance were one foot.

Parker’s heat shield, designed to withstand temperatures up to 2,500°F (1,370°C), has so far only faced about 2,000°F (1,090°C) — a pleasant surprise for engineers, whose instruments located just behind the shield remain near room temperature.

A Glimpse into the Solar Corona

Using its onboard Wide-Field Imager for Solar Probe (WISPR), Parker recorded high-resolution images of coronal mass ejections (CMEs) – massive bursts of solar particles responsible for space weather phenomena like the stunning global auroras seen in May 2024.

“What we saw were CMEs stacking on top of each other – a truly rare and incredible sight,” said Rawafi.

The images also revealed detailed patterns of the heliospheric current sheet – a spiraling, invisible boundary where the Sun’s magnetic field flips polarity. This structure is crucial for understanding how solar eruptions travel through the solar system and impact Earth.

The Real-World Impact

The Sun’s violent behavior affects more than just scientific curiosity. Space weather can disrupt satellite communications, knock out power grids, and jeopardize astronaut safety. As more satellites are launched in the coming years, precise understanding of solar effects will be vital to prevent orbital collisions and system malfunctions.

Rawafi noted that some of the most extreme solar storms historically occur during the declining phase of the Sun’s 11-year cycle — a phase we’re approaching in the next five to six years. The infamous Halloween Solar Storms of 2003 are one example of the chaos such events can cause.

Parker’s Ongoing Journey

With ample fuel remaining, Parker may continue to operate for decades, well beyond initial expectations. When the spacecraft can no longer power itself, it will eventually disintegrate, becoming — as Rawafi poetically put it — “part of the solar wind itself.”

These new images mark a transformative moment in heliophysics, deepening our understanding of the Sun and bolstering efforts to protect Earth and its growing space infrastructure from solar threats.